|

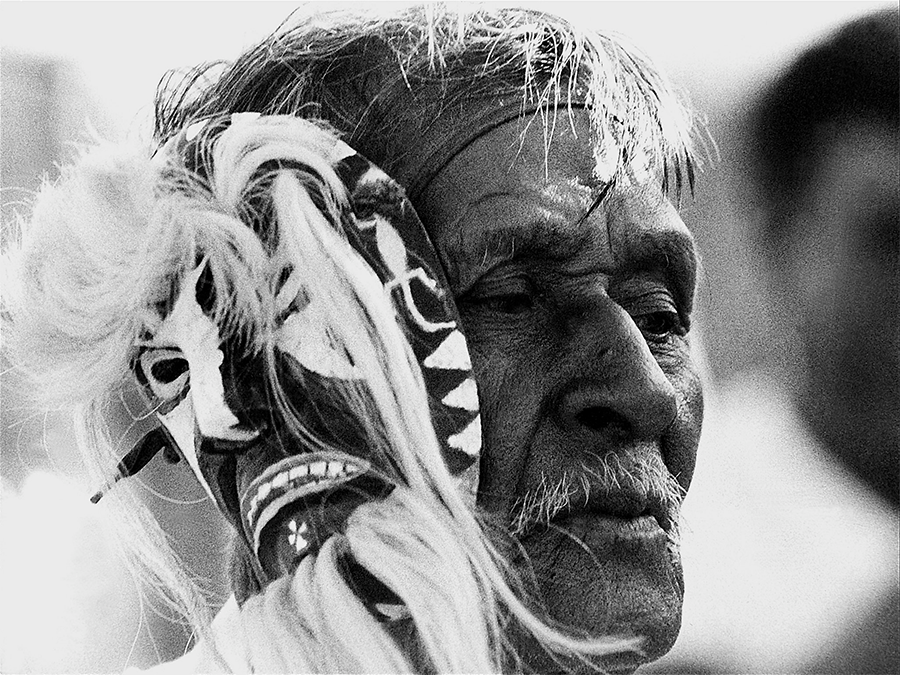

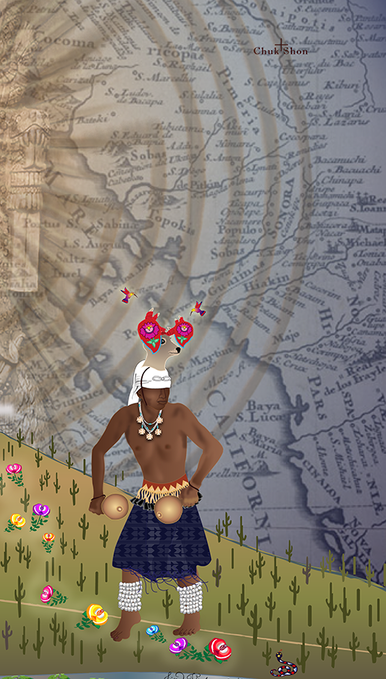

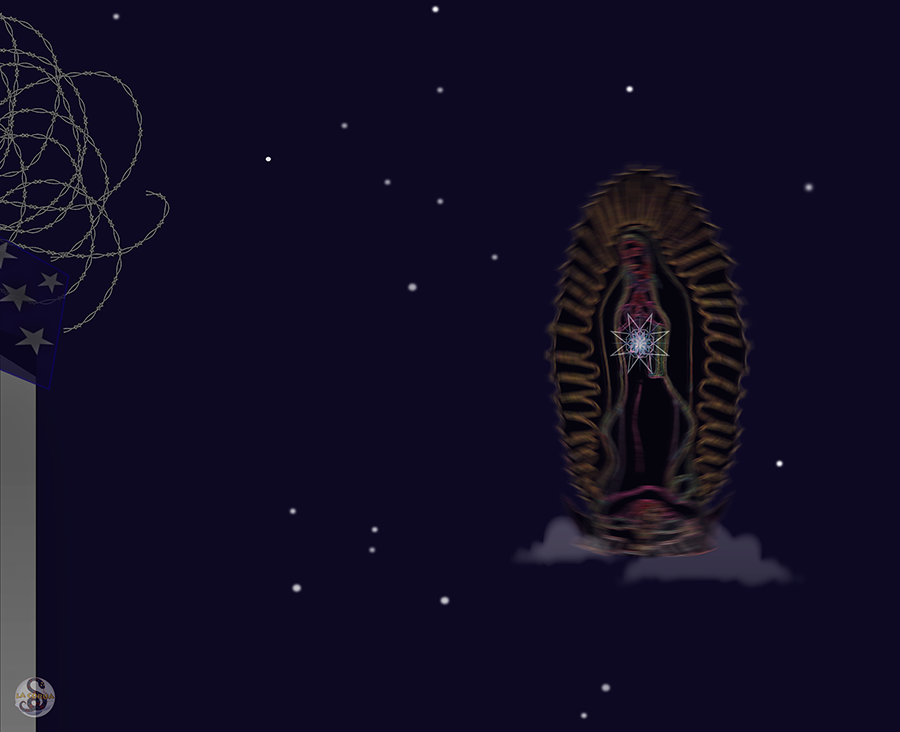

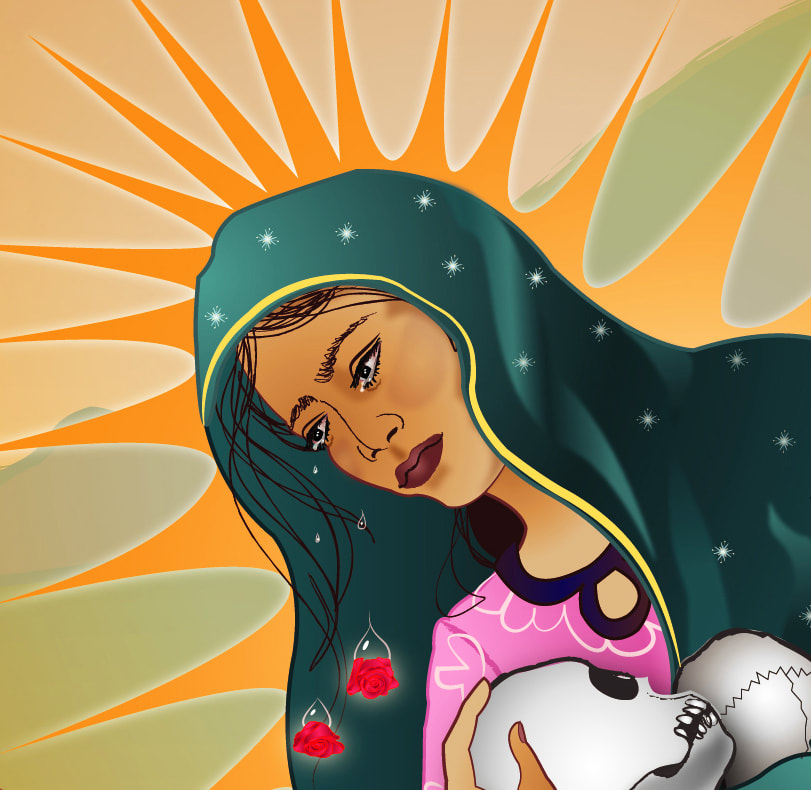

Continued from Home Page: For original residents - Mexican, Native, Chinese and African Americans, remaining in their home barrios around the A-Mountain area today is challenging. Poverty continues its downward grind on residents not eligible for opportunities and resources. Arizona's libertarian laws cater to high-end investors (often out-of-state) and have made massive changes to the Greater Tucson area through the years. It is a system long favoring whites over minorities, and eclipses local laws and ordinances. Existing inhabitants have been evicted or bought out on the cheap-- taking with them the cultural richness and living history that made their real estate so coveted by outsiders. Yet, silently, eternally, guardians of The People, and of The Earth are here. They do not prevent changes, but they are here and are not forgotten. And they have been here since the beginning. They plant the seeds of survival and wisdom in every new generation. Tucson's spiritual heritage is a unique amalgamation of Tohono O'odham and Mexican Catholicism coexisting without the bloody subjugations that defined other regions of the American Southwest. It became further enriched as waves of Pascua Yaqui (Yoeme) Indians migrated from their homelands in Sonora escaping genocide by President Porfirio Diaz of Mexico, bringing their own earth cosmology mixed with Catholicism absorbed from Jesuit priests in the 1600's. I'itoiThe master guardian spirit of the Tucson region, the one who was here first is I'itoi; the creator of the O'odham people and their ancestors the Hohokam ("the People Who Are Gone"). He brought the people up like children and gave them the gift of the Himdag, a set of commandments guiding them to live in balance with the world and interact with it as intended. A timeless entity assuming a number of powerful forms in tribal legend, he retired from the world and lives as a little old man in a cave beneath Baboquivari Peak - the original place of emergence from which he led his people out of the underworld after a great flood. I'itoi's people have inhabited this land for over 10,000 years, and they believe he watches over them today; their 'Older Brother' from his sacred home beneath Baboquivari Peak, which they regard as the center of their universe. I'itoi is most often referred to as the 'Man in the Maze': an ancient design in O'odham petroglyphs, basketry and jewelry. He is the figure at the top of a labyrinth: the symbol for life's path a person travels and the encounters that impact him and direct him to reach the center where he is blessed by the sun god before passing into the next world. The O'odham have been stewards of the Sonoran Desert since before time was time. Faces of the Tohono O'odham Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe Before the Spanish conquerors arrived on the shores of Mexico, the famous mother deity we know as Our Lady of Guadalupe commonly went by the Nahuatl names Tonantzin and Coatlaxopeuh to the Aztecs of Tenochtitlan, in the Valley of Mexico. She was known in many forms: "Our Great Mother", "Honored Grandmother", "Mother of Earth and Corn", "Our Lady who emerges from the region of light like the eagle from fire", and “the one who has dominion over serpents”. The Aztecs built a shrine to her and other fertility goddesses on a hill they called Tepeyac, and had long been worshiped her there. When the Spaniards arrived, the shrine was demolished and people were forbidden to go there. The era of the Spanish conquests was drenched in blood and death. Appalled by the savage Aztec rituals of human sacrifice, the conquistadors ruthlessly crushed the Aztec empire of Tenochtitlan, decimated the population with smallpox, and pressed the masses into Catholicism. A short version of the legend of Our Lady of Guadalupe goes something like this: One day in the 16th century, a poor Indian Catholic convert named Juan Diego was passing by Tepeyac Hill when he spotted a glowing apparition on its summit. Approaching, he saw it was a dark-skinned Indian woman with stars on her cloak, a crown on her head, the moon supporting her, the rays of the sun surrounding her-- and, she was pregnant. She told him that she loved the people very much and wanted to protect them, and she asked him to have a new church built for her on the site. Juan protested, saying that the bishop would never believe he had seen her. The lady pointed, and suddenly among the cactus grew roses, a flower foreign to the New World and the flower of the heart. Juan gathered the roses in his tilma and, going straight to the bishop, unrolled the cloak. Then an even greater miracle happened: an image of the pregnant indigenous Virgin Mary appeared with the roses on the rough agave fiber cloth. Truly, she was Queen of Heaven. This Great Compassionate Mother offered a refuge from the new angry Christian God, and by extension the early Christian invaders. Adopted as Mexico's patron saint, she became a symbol for freedom and resistance to continued foreign intervention. The Virgin of Guadalupe came to the Pimeria Alta with Padre Eusebio Kino and the first Spanish settlers. Through the centuries, Guadalupe/Tonantzin has risen to become Queen of the Americas, and her compassionate embrace extends far beyond the Catholic Church. She stands for boundless love and the enduring rights of the marginalized and oppressed everywhere. Yoeme / Pascua Yaqui , The Yaqui Indians, or Yoeme (The People) are a Uto-Aztecan speaking indigenous tribe who inhabit the valley of the Río Yaqui in the Mexican state of Sonora. Following Mexican independence in 1821, the regime of Porfirio Diaz attempted to seize control of Yaqui farm lands and, for ninety years, Yaqui guerrilla fighters resisted attacks by the Mexican government. The Mexican army finally defeated the Yaqui at the battle of Buatachive in 1886. Many Yaquis fled into Southern Arizona and settled in small colonias (communities) around Tucson. Those remaining in Mexico were systematically selected for genocide-- either through slavery or direct extermination. Their population dropped from 20,000 to less than 3,000. Today in Mexico, the remaining Pascua Yaqui struggle to survive -- and, although they have finally been acknowledged by the government for historical injustices, Sonora's capital Hermosillo, continues to drain their precious Rio Yaqui and sole source of water dry-- without compensation. For their protests, they live under constant threat and many of their leaders have been assassinated. On this side of the border, the Yaqui achieved official tribal status in 1978, along with a small reservation southwest of Tucson, and continue to live in their original barrio communities around Southern Arizona. They keep their culture alive with the same pride and resilience that has defined them as a people for millennia. The heart of Yoeme cosmology lies in five enchanted worlds that mirror the natural world in which we live. These mystical realms are an integral part of everyday life for the Yaqui people. One of the most important worlds is the Sea Ania or Flower World. The flowers of the Sea Ania unite the Yoeme and connect them to their past. The deer dance is an important ceremony that lets Yaqui people communicate with the Flower World. It is performed at Easter, as well as other times of the year. In the deer dance, Saila Maaso (little brother deer) leaves the Flower World to visit the Yaqui people. Hummingbirds are especially sacred to the Yoeme and are revered as messengers from the spirit to the natural world. Much Yoeme ritual is centered upon balancing these worlds and lessening the harm done to them by human beings. The Yaqui have combined these beliefs with their unique practice of Catholicism, and, much like the Hopis, take the burden of our world upon themselves through active ceremony as exemplified in their practice of Cuaresma (Lent) and Pascua (Easter). The Yoeme continue their traditions of stewardship and prayer for humanity on this side of the border, with help from the dedication of surviving cultural teachers like Pascola mask carver, Louis David Valenzuela. The roses honor his carving style.

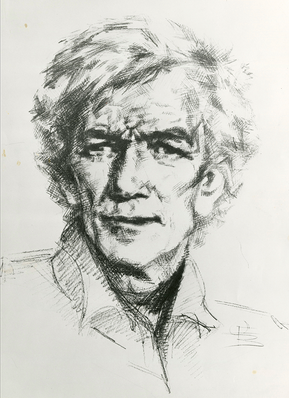

Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino No one has left a more lasting legacy in the Pimeria Alta than Eusebio Francisco Kino, the Jesuit missionary "cowboy" priest. Father Kino's era was relatively short--from 1687 through 1711-- but over those 24 years he covered over 50,000 miles on horseback, interacted with 16 different indigenous tribes and founded 26 missions. It was Padre Kino who worked with the already agricultural indigenous native peoples, introducing them to cattle, sheep and goats, the Spanish Barb horse, and European fruits, seeds, and herbs. Kino opposed slavery and compulsory hard labor that the Spaniards forced on native people, causing great controversy among his co-missionaries--most of whom adhered to the laws imposed by Spain on their territory. He viewed native peoples as human beings and treated them as such; leaving a legacy divergent from the one of violence and subjugation the Catholic Church is known for in Mexico and the Southwest. Kino built missions extending from the present day states of Mexican Sonora into present-day Arizona, where Mission San Xavier del Bac south of Tucson is still a functioning Franciscan parish church. Little remains of most of the others, but a few are still standing, such as the Mission at Tumacacori, 25 miles south of Tucson, now a historic national monument. (Seasonal open-air binational masses are held there, along with regional celebrations and fiestas.) Kino also constructed nineteen rancherias (villages), brought the first cattle to the region, and became known as the Pimeria Alta's first rancher. He also introduced European grains and seeds that provided Northern Mexico with wheat and the old world herbs we all enjoy today. An advanced cartographer for his time, he followed ancient trading routes established millennia prior by the natives. These trails were later expanded into roads. His many expeditions on horseback covered over 50,000 square miles, during which he mapped an area 200 miles long and 250 miles wide. Kino's maps were the most accurate maps of the region for more than 150 years after his death. Many of today's geographical features, including the Colorado River were first named by Kino. Kino practiced other crafts and was reportedly an expert astronomer, mathematician and writer, authoring books on religion astronomy and cartography. Kino remained among his missions until his death. He died from fever on 15 March 1711 at age 65, in what is present-day Magdalena de Kino, Sonora, Mexico. His skeletal remains can be viewed in his crypt, which is a national monument of Mexico. Apart from the usual monuments and street names, Padre Kino's presence and imprint is everywhere here. Most well known is the annual binational pilgrimage and fiesta at Magdalena de Kino, in Mexico in early October. Catholic Mexicans, Tohono O'odham, Yoeme, and even tenacious white people walk (some ride horseback) from Sonoran Arizona to the church where his remains are buried and pay homage to Kino's patron saint, San Xavier. There are also binational cabalgatas (pack-horse camp rides) retracing Kino's original trails in devotion to his cause for sainthood. (See Por Los Caminos de Kino)

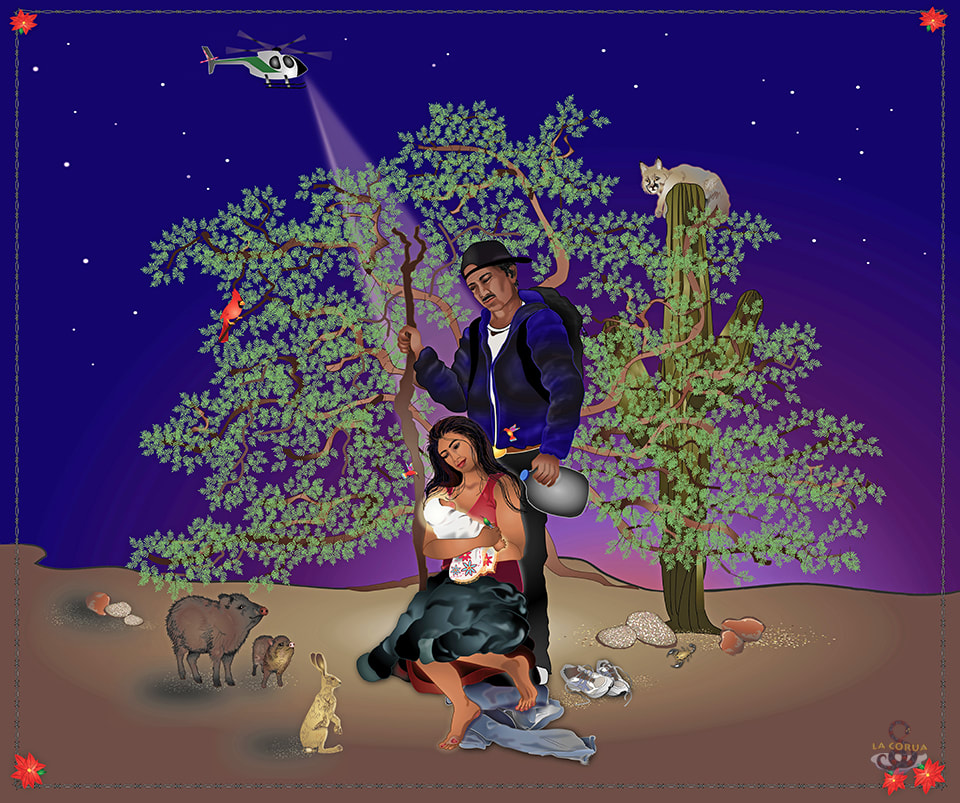

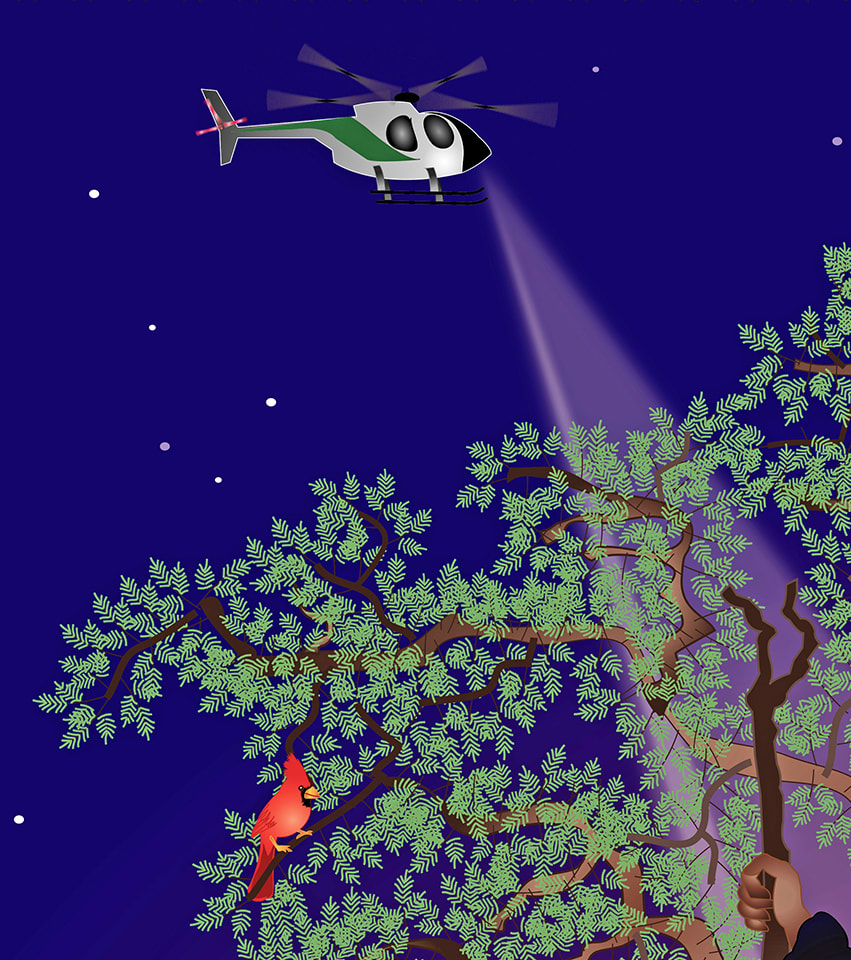

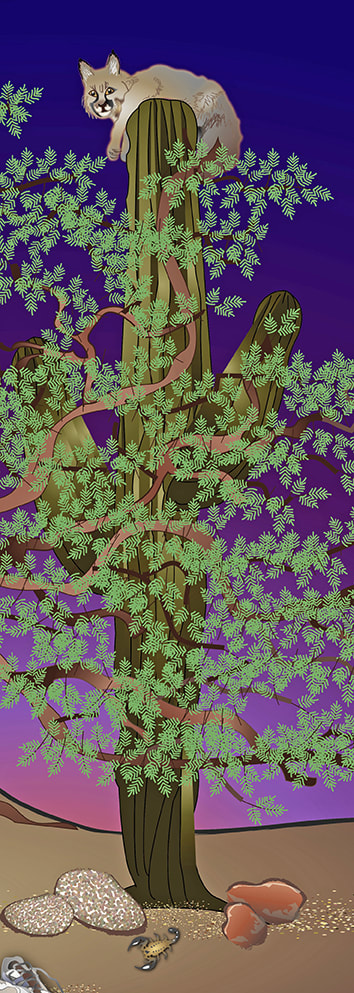

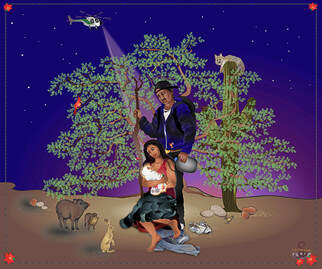

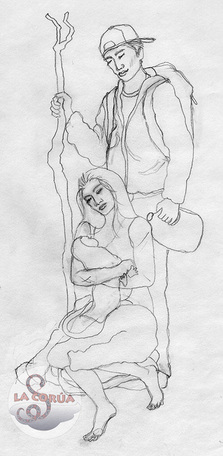

Arizona has been called "America's Meth Lab of Democracy". Many hot button issues were tried here first and have since gone national-- on steroids. One of them is Nativism. Back in 2013, I did a painting called, Navidad Baja Arizona - A Christmas Story. It was my response to the dehumanization of immigrants dying in our desert, and how women were accused of coming here to have "anchor babies" and game our system. Fear and victim-blaming is a highly successful weapon as old as time and in Arizona, each generation breeds eager ears and new wrestless trigger fingers. Enter the Trump brand of Nativism and by 2019, it's a whole new ballgame. This Christmas, I didn't need to reinvent the wheel. I merely deported the Holy Couple, placing them in a Mexican border camp surveilled by ruthless realities. I want to offer up the idea that the Nativity is really about the persistence of the Human Spirit. Regimes come and go. Although ephemeral, the human spirit finds a way. Always. - Linda Magdalena Victoria  In this homage, it is my intent to reach beyond the political wailing and gnashing of teeth to remind us that the Divine often comes through via the "least of these". The Christmas story has many parallels to the struggles of present day migrants crossing Arizona. It is my way of blending both historical and true-to-life contemporary elements, and of putting a human face on the "aliens" among us. My story goes like this: The treacherous journey through Mexico and into the Sonoran desert overcomes the pregnant Maria, and she goes into labor. The pollero (coyote) of her group leaves her to fend for herself. She seeks shelter under the spreading branches of a mesquite tree. Maria sits on her backpack, covered by her jacket. Her bare feet have blisters from many miles of walking. The man Jose is older than Maria and could be her husband, a relative, or a sympathetic fellow crosser. He wears dark clothing and the iconic back-pack with a gallon jug of water. In his right hand is a staff hewn from a mesquite branch, which may also indicate he's made this trek before. Maria wraps the newborn Jesus in a bordado (hand-embroidered tortilla cloth) -- a memento given by her mother back home for her new life in the E.E.U.U. (United States). Hummingbirds are an auspicious blessing in most indigenous cultures, and three of them visit the baby. The birth of this tiny human stirs the curiosity of some local desert wildlife... a javelina and her baby and a jackrabbit look on. A bobcat gazes from atop a saguaro behind the mesquite tree. ( Yes, they really do hang out on top of saguaros!) Crawling from the rocks towards Maria's battered shoes is a scorpion - a reminder that life is a precarious journey. (A scorpion logo also appears on many cartel drug packages.) Instead of a star, there is a Border Patrol helicopter. It is not clear whether it has discovered Jose & Maria's hiding place... Navidad en Arizona is part of the vision I seek to portray through art: a compassion that can stand in awe of what "the least of these" carry -- rather than stand in judgement of how they carry it. - Linda Magdalena Victoria  Of all the seasons of the year, Fall is my favorite. Here in the Sonoran Desert the temperatures begin to cool and there is a restful stillness in the air. Around the world, many cultures celebrate this time as the annual window when the veil between the spirit and physical world is the thinnest. In pre-Christian times, death was not a thing to be feared but a transition to be celebrated as another form of life. In this way, family members and ancestors were honored and kept close in the hearts of the living. During this special fall window, many grand occurrences take place in nature that have helped people connect with those who have passed on. In North America, one of the most phenomenal is the mass migration of the Monarch butterfly. Every year, 60 million-one billion Monarchs make the journey from eastern Canada to the forests of western central Mexico. They arrive in the state of Michoacán every fall. The Purépecha Indians in the region have noticed the arrival of monarchs since pre-Hispanic times. In the native Purépecha language, the monarch butterfly is called the harvester butterfly, because monarchs appear when it's time to harvest the corn. Monarchs and the Mexican holiday Day of the Dead (El Día de los Muertos) also occurs when the monarchs appear. According to traditional belief, the monarchs are the souls of ancestors who are returning to Earth for their annual visit. All Souls/All Saints/Day of the Dead occurs officially on November 2nd. In Mexico, however, it is a three-day celebration that begins on October 31st. More on this festive tradition next post.  The Virgin of Guadalupe is Mexico's patron saint and is loved and revered throughout the America's. Here, her tears turn into roses that rain down as a blessing on the deceased. (Roses are a key element in her legend, read more about her here.) Roses are also important to the Yoeme (Pascua Yaqui) cultural belief in the Flower World; their spiritual vision of heaven. The presence of an owl portends death, according Mexican folk traditions. There is an old saying in Mexico: Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere ("When the owl cries/sings, the Indian dies"). The Aztecs and Maya, along with other Natives of Mesoamerica, considered the owl a symbol of death and destruction. The saguaro cactus has finished its spring bloom and is ready for the saguaro harvest conducted by the Tohono O'odham Indians in late June. From the saguaro fruit they make saguaro wine, jams, and jellies and have a rain feast in honor of the coming monsoon. The horned lizard at the bottom does not have any special meaning except that they are a beloved endangered desert critter. Sonoran Arizona remains America's migrant graveyard. Nativist immigration policies have become more and more untethered in recent decades in a lust to grow the new industrial for-profit private prison complex. Meanwhile, the American economy still depends on immigrant labor, now more than ever - to feed us, and do the jobs Americans never have, and never will do. I continue to find ways where I can honor all those who gave up everything for a better life. It is my intent to show here that we can only hope they are being received into a better place than those they knew in their home countries or in our deserts. Ca nel nehuatl in namoicnohuacanantzin in tehuatl ihuan in ixquichtin in ic nican tlalpan ancepantlaca, ihuan in occequin nepapantlaca notetlazotlacahuan, in notech motzatzilia, in nechtemoa, in notech motechilia … True indeed. Everything I am and do is rooted in love of our land and its people, and our Mother. Her mantle has room for everyone. And 'She Comes for Them'... Over the past ten years, more than 4,000 people have died while crossing the Arizona desert to find jobs, join families, or start new lives. Other migrants tell of the corpses they pass—bodies that are never recovered or counted. Crossing With the Virgin collects stories heard from migrants about these treacherous treks—firsthand accounts told to volunteers for the Samaritans, a humanitarian group that seeks to prevent such unnecessary deaths by providing these travelers with medical aid, water, and food. |