|

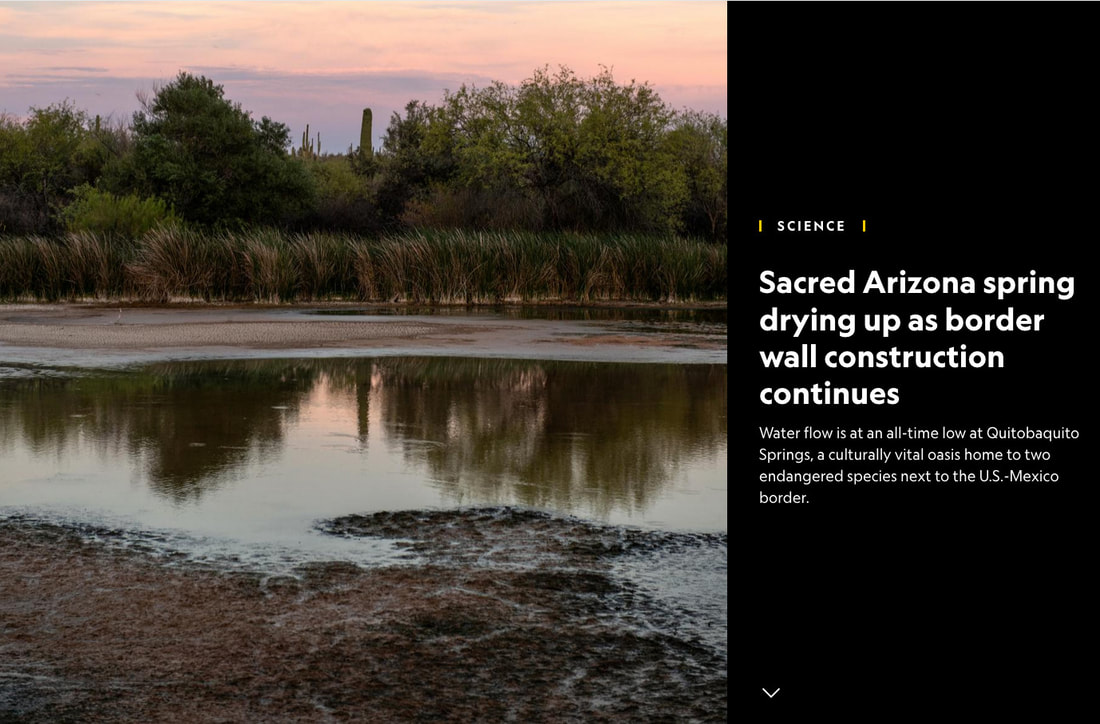

This piece of normalized recklessness and profiteering jumped out at me recently. A July pictorial in The National Geographic about Trump's border wall captured the essence of why guardian spirits like La Corua and ancient gifts from I'itoi (O'odham Elder Brother) are meaningless to those who "take no responsibility". Beautifully written by Douglas Main with powerful imagery by photographer Ash Ponder, I share snippets that speak to the heart of the Living Being that is the Sonoran Desert and the decimation of both land and culture that its guardian people, the O'odham, now face. I hope you will follow the link to view and read the whole thing... It speaks to a critical tipping point for an area that exists nowhere else in the world. When it's gone, it's gone. And for what? To make a few white men rich and feed an emperor's vanity. A classic, wretched old story... White Man's ignorance is a dead-end road. We are already there-- but long as there is mud in the pond, we will continue to scrape. Sacred Arizona spring drying up as border wall construction continues

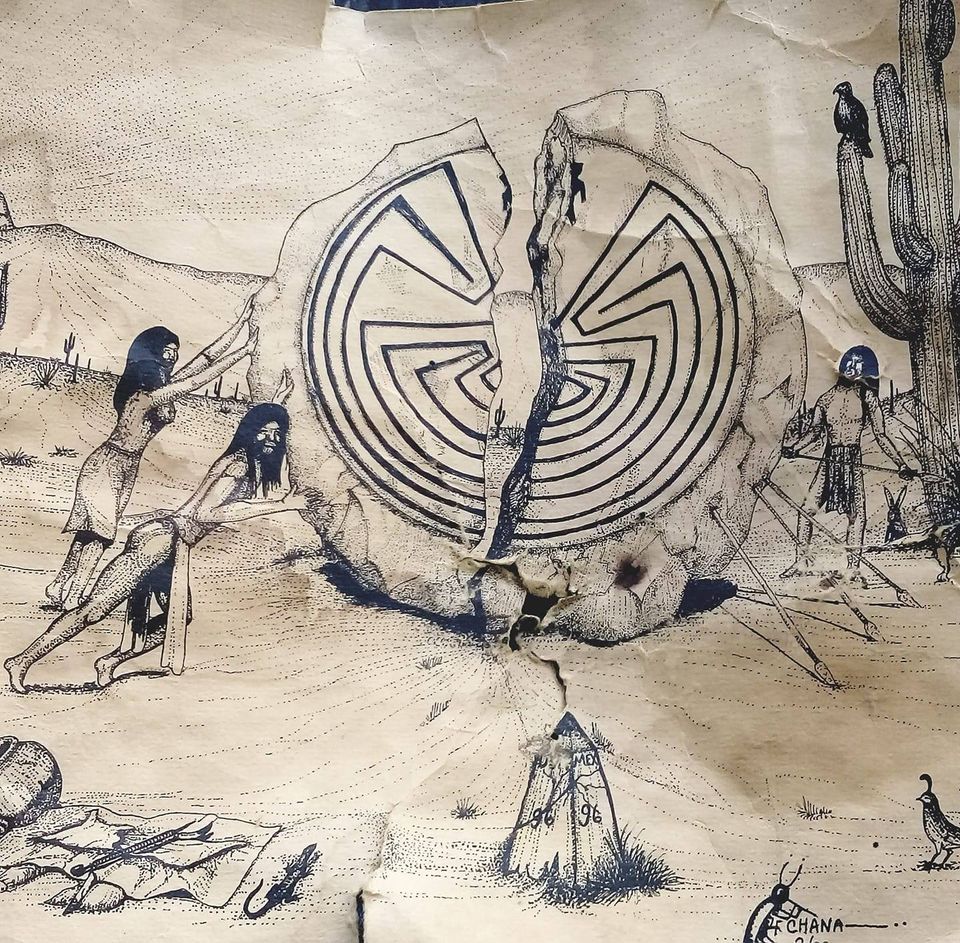

"On Each side the people hold it together, to share M Himadag, O'odham" |

| There's a fabulous little treasure of a book to learn about the O'odham Children's Shrine, their sacred mountain--home to I'itoi, Their legends and creation stories, the Yaquis (Yoeme), Native Christianities, La Corua, and other rich stuff: Beliefs and Holy Places - A Spiritual Geography of the Pimeria Alta, by James S. ("Big Jim" ) Griffith |

Imelda is my interpretation of a desert wise-woman and healer. She came to me as inspiration from a real-life curandera named Huila in Luis Alberto Urrea's novel, The Hummingbird's Daughter.

Imelda walks barefoot with Mother Earth through a Sonoran sky-island landscape. The saguaro cactus is in the midst of spring bloom, surrounded by Gobernadora (creosote bush). Edging up the hillside is a gnarly old mesquite tree with a great horned owl gazing at her in the distance. (In indigenous folklore, owls are believed to portend death; but I present it here as the symbol of transition, ready to help Imelda guide spirits of the suffering to the Spirit or Flower World.)

She walks with reverence to all living things and gazes fondly at the life she sees around her. She is greeted by hummingbirds, a horned lizard, and creatures of the spring; including a dragon fly. I gave the turtle a mystical quality because I see her as the spirit of my own artist mother who loved turtles. Another mystical, mythical creature is the water-serpent, La Corúa. A vanishing folktale of the Sonoran borderlands tells of La Corúa: a large water snake with a cross on its forehead that guards the spring and cleans the veins of water with its fangs. It is believed that if you kill the Corúa the spring will dry up.*

Imelda wears a simple long huipil similar to those worn by the women in Vera Cruz but with embroidered flowers typical to the Yoeme (Pascua Yaqui) tribe. Around her neck is an Ojo de Venado (Dear Eye), a talisman to guard against evil spirits, and a handmade rosary with La Virgen de Guadalupe and shells for each mystery. She wears a golden rebozo (shawl) and a satchel for herbs and other healing talismans she finds.

Plants of medicinal significance:

Imelda is carrying Arizona/Summer poppies or Baiborín (Kallstroemia grandiflora) - used for fatigue, body pains, fever ... and mange in animals. Growing along the spring is a Passion-fruit vine (Passiflora mexicana) or Pasionaria, which grows in canyons of Southeastern Arizona and Mexico. A sedative, it quiets respiration and blood pressure.

The Gobernadora (Creosote bush), one of the most common, widely dispersed plants of the Desert Southwest, and has many medicinal properties. When applied as a salve to the skin, chaparral slows down the rate of bacterial growth and kills it with its antimicrobial activity.

Lastly is Toloache, Sacred Datura (Datura meteloides). Though highly toxic, this is one of the most beautiful plants of the Southwest. According to the Seri tribe, Datura was one of the first plants ever created. Therefore, it is said that humans should avoid contact with the plant as it is extremely sacred. Only shamans use the plant, as inappropriate use can be very dangerous. The Mixteca of Oaxaca, Mexico, believe that the plant spirit of Datura is an elderly wise woman.

*Tucson’s internationally renown folklorist, “Big Jim” Griffith has kept the tale of La Corúa alive through the years, and it became the inspiration for the name of my art business.)

Imelda walks barefoot with Mother Earth through a Sonoran sky-island landscape. The saguaro cactus is in the midst of spring bloom, surrounded by Gobernadora (creosote bush). Edging up the hillside is a gnarly old mesquite tree with a great horned owl gazing at her in the distance. (In indigenous folklore, owls are believed to portend death; but I present it here as the symbol of transition, ready to help Imelda guide spirits of the suffering to the Spirit or Flower World.)

She walks with reverence to all living things and gazes fondly at the life she sees around her. She is greeted by hummingbirds, a horned lizard, and creatures of the spring; including a dragon fly. I gave the turtle a mystical quality because I see her as the spirit of my own artist mother who loved turtles. Another mystical, mythical creature is the water-serpent, La Corúa. A vanishing folktale of the Sonoran borderlands tells of La Corúa: a large water snake with a cross on its forehead that guards the spring and cleans the veins of water with its fangs. It is believed that if you kill the Corúa the spring will dry up.*

Imelda wears a simple long huipil similar to those worn by the women in Vera Cruz but with embroidered flowers typical to the Yoeme (Pascua Yaqui) tribe. Around her neck is an Ojo de Venado (Dear Eye), a talisman to guard against evil spirits, and a handmade rosary with La Virgen de Guadalupe and shells for each mystery. She wears a golden rebozo (shawl) and a satchel for herbs and other healing talismans she finds.

Plants of medicinal significance:

Imelda is carrying Arizona/Summer poppies or Baiborín (Kallstroemia grandiflora) - used for fatigue, body pains, fever ... and mange in animals. Growing along the spring is a Passion-fruit vine (Passiflora mexicana) or Pasionaria, which grows in canyons of Southeastern Arizona and Mexico. A sedative, it quiets respiration and blood pressure.

The Gobernadora (Creosote bush), one of the most common, widely dispersed plants of the Desert Southwest, and has many medicinal properties. When applied as a salve to the skin, chaparral slows down the rate of bacterial growth and kills it with its antimicrobial activity.

Lastly is Toloache, Sacred Datura (Datura meteloides). Though highly toxic, this is one of the most beautiful plants of the Southwest. According to the Seri tribe, Datura was one of the first plants ever created. Therefore, it is said that humans should avoid contact with the plant as it is extremely sacred. Only shamans use the plant, as inappropriate use can be very dangerous. The Mixteca of Oaxaca, Mexico, believe that the plant spirit of Datura is an elderly wise woman.

*Tucson’s internationally renown folklorist, “Big Jim” Griffith has kept the tale of La Corúa alive through the years, and it became the inspiration for the name of my art business.)

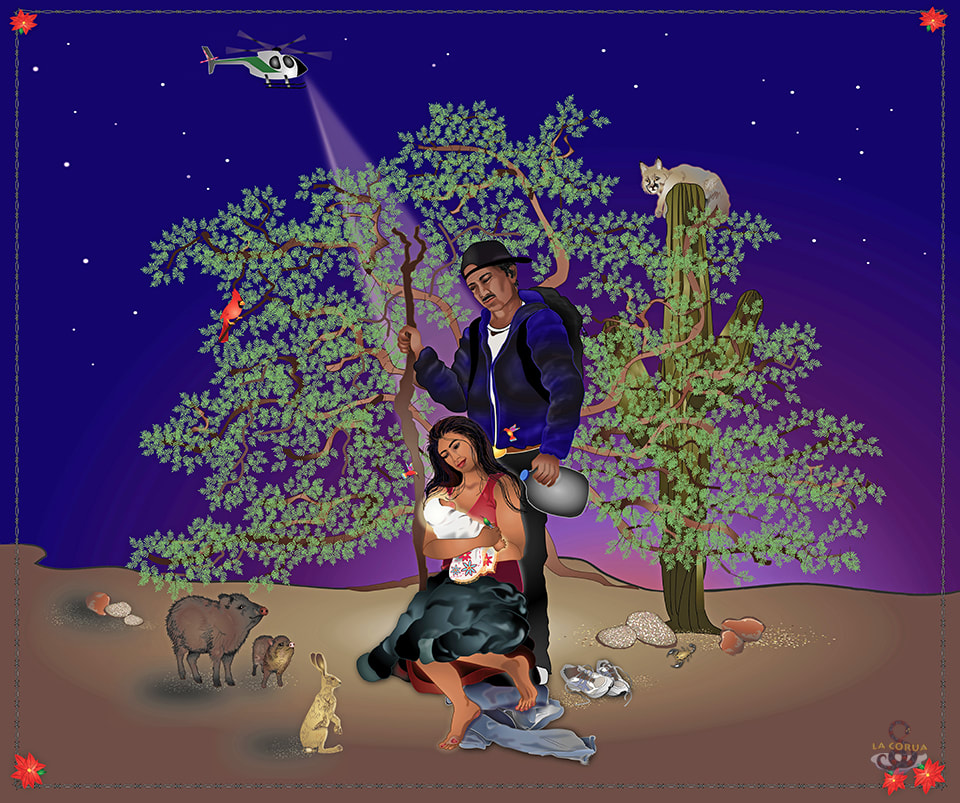

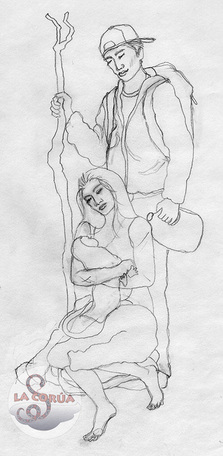

In this homage, it is my intent to reach beyond the political wailing and gnashing of teeth to remind us that the Divine often comes through via the "least of these". The Christmas story has many parallels to the struggles of present day migrants crossing Arizona. It is my way of blending both historical and true-to-life contemporary elements, and of putting a human face on the "aliens" among us. My story goes like this:

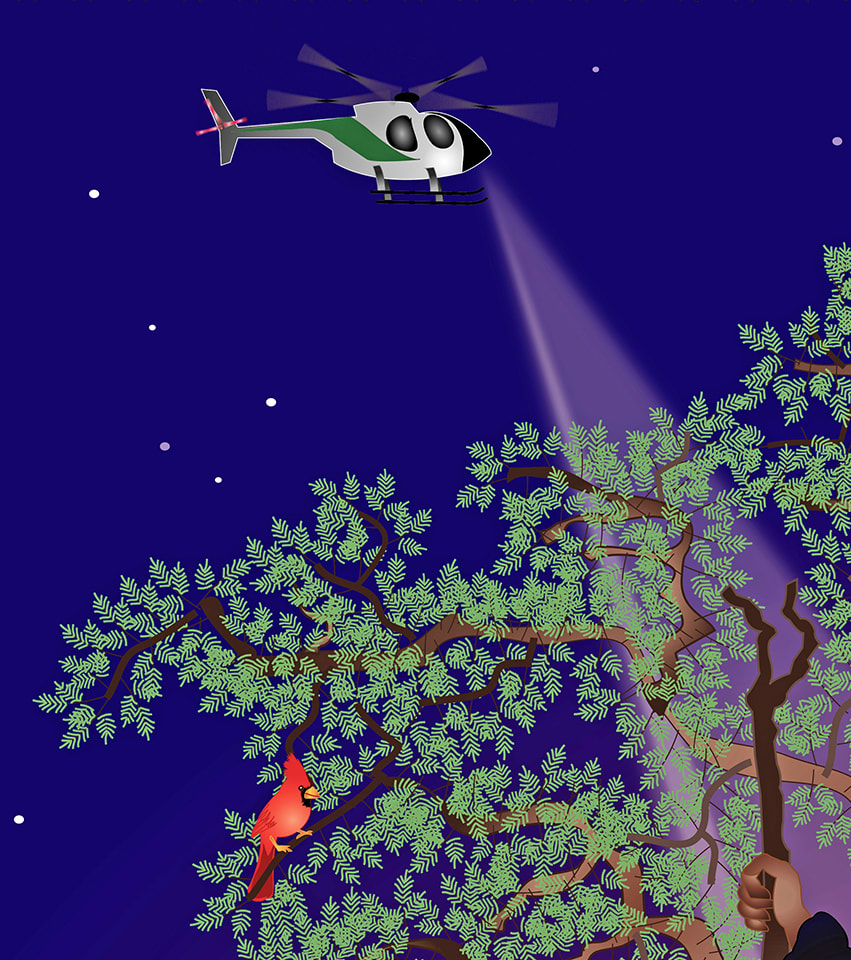

The treacherous journey through Mexico and into the Sonoran desert overcomes the pregnant Maria, and she goes into labor. The pollero (coyote) of her group leaves her to fend for herself. She seeks shelter under the spreading branches of a mesquite tree.

Maria sits on her backpack, covered by her jacket. Her bare feet have blisters from many miles of walking. The man Jose is older than Maria and could be her husband, a relative, or a sympathetic fellow crosser. He wears dark clothing and the iconic back-pack with a gallon jug of water. In his right hand is a staff hewn from a mesquite branch, which may also indicate he's made this trek before.

Maria wraps the newborn Jesus in a bordado (hand-embroidered tortilla cloth) -- a memento given by her mother back home for her new life in the E.E.U.U. (United States). Hummingbirds are an auspicious blessing in most indigenous cultures, and three of them visit the baby.

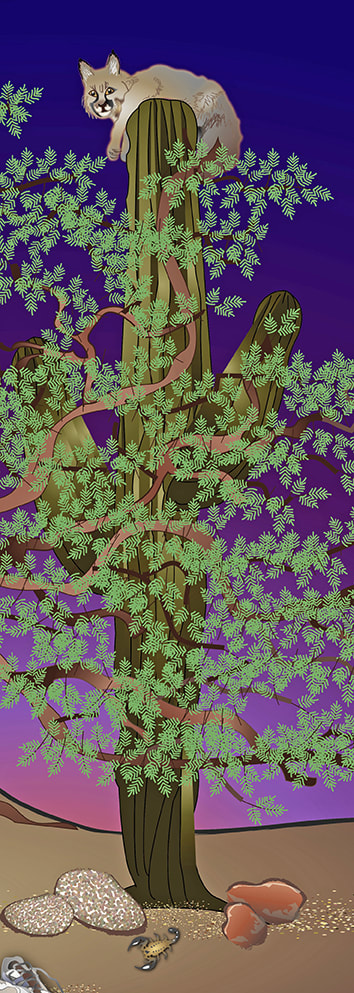

The birth of this tiny human stirs the curiosity of some local desert wildlife... a javelina and her baby and a jackrabbit look on. A bobcat gazes from atop a saguaro behind the mesquite tree. ( Yes, they really do hang out on top of saguaros!) Crawling from the rocks towards Maria's battered shoes is a scorpion - a reminder that life is a precarious journey. (A scorpion logo also appears on many cartel drug packages.)

Instead of a star, there is a Border Patrol helicopter. It is not clear whether it has discovered Jose & Maria's hiding place...

Navidad en Arizona is part of the vision I seek to portray through art:

a compassion that can stand in awe of what "the least of these" carry -- rather than stand in judgement of how they carry it.

- Linda Magdalena Victoria

The treacherous journey through Mexico and into the Sonoran desert overcomes the pregnant Maria, and she goes into labor. The pollero (coyote) of her group leaves her to fend for herself. She seeks shelter under the spreading branches of a mesquite tree.

Maria sits on her backpack, covered by her jacket. Her bare feet have blisters from many miles of walking. The man Jose is older than Maria and could be her husband, a relative, or a sympathetic fellow crosser. He wears dark clothing and the iconic back-pack with a gallon jug of water. In his right hand is a staff hewn from a mesquite branch, which may also indicate he's made this trek before.

Maria wraps the newborn Jesus in a bordado (hand-embroidered tortilla cloth) -- a memento given by her mother back home for her new life in the E.E.U.U. (United States). Hummingbirds are an auspicious blessing in most indigenous cultures, and three of them visit the baby.

The birth of this tiny human stirs the curiosity of some local desert wildlife... a javelina and her baby and a jackrabbit look on. A bobcat gazes from atop a saguaro behind the mesquite tree. ( Yes, they really do hang out on top of saguaros!) Crawling from the rocks towards Maria's battered shoes is a scorpion - a reminder that life is a precarious journey. (A scorpion logo also appears on many cartel drug packages.)

Instead of a star, there is a Border Patrol helicopter. It is not clear whether it has discovered Jose & Maria's hiding place...

Navidad en Arizona is part of the vision I seek to portray through art:

a compassion that can stand in awe of what "the least of these" carry -- rather than stand in judgement of how they carry it.

- Linda Magdalena Victoria

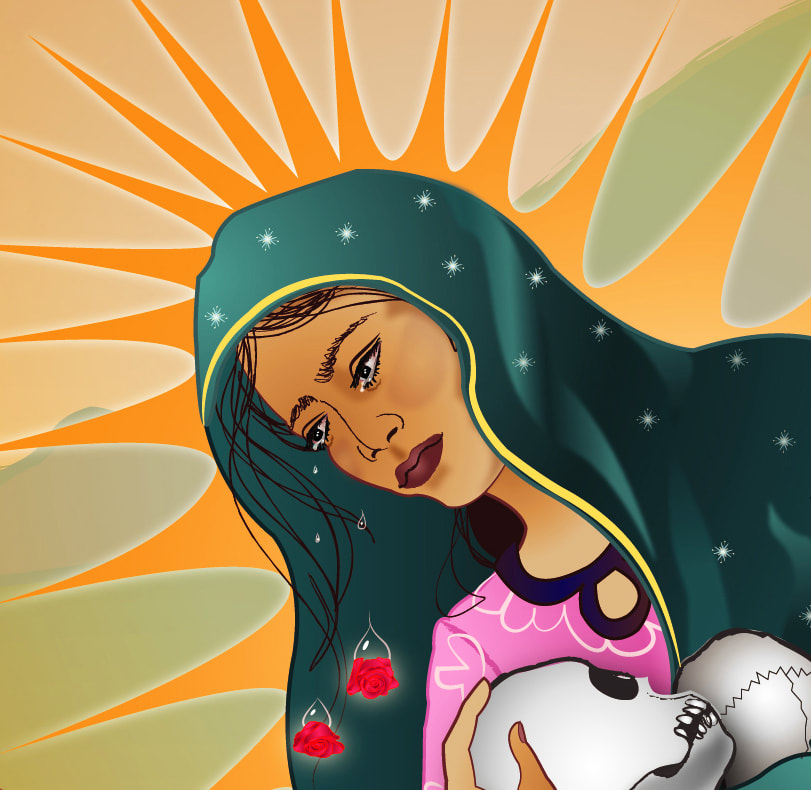

The Virgin of Guadalupe is Mexico's patron saint and is loved and revered throughout the America's. Here, her tears turn into roses that rain down as a blessing on the deceased. (Roses are a key element in her legend, read more about her here.) Roses are also important to the Yoeme (Pascua Yaqui) cultural belief in the Flower World; their spiritual vision of heaven.

The presence of an owl portends death, according Mexican folk traditions. There is an old saying in Mexico: Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere ("When the owl cries/sings, the Indian dies"). The Aztecs and Maya, along with other Natives of Mesoamerica, considered the owl a symbol of death and destruction.

The saguaro cactus has finished its spring bloom and is ready for the saguaro harvest conducted by the Tohono O'odham Indians in late June. From the saguaro fruit they make saguaro wine, jams, and jellies and have a rain feast in honor of the coming monsoon.

The horned lizard at the bottom does not have any special meaning except that they are a beloved endangered desert critter.

Sonoran Arizona remains America's migrant graveyard. Nativist immigration policies have become more and more untethered in recent decades in a lust to grow the new industrial for-profit private prison complex. Meanwhile, the American economy still depends on immigrant labor, now more than ever - to feed us, and do the jobs Americans never have, and never will do.

I continue to find ways where I can honor all those who gave up everything for a better life. It is my intent to show here that we can only hope they are being received into a better place than those they knew in their home countries or in our deserts.

The presence of an owl portends death, according Mexican folk traditions. There is an old saying in Mexico: Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere ("When the owl cries/sings, the Indian dies"). The Aztecs and Maya, along with other Natives of Mesoamerica, considered the owl a symbol of death and destruction.

The saguaro cactus has finished its spring bloom and is ready for the saguaro harvest conducted by the Tohono O'odham Indians in late June. From the saguaro fruit they make saguaro wine, jams, and jellies and have a rain feast in honor of the coming monsoon.

The horned lizard at the bottom does not have any special meaning except that they are a beloved endangered desert critter.

Sonoran Arizona remains America's migrant graveyard. Nativist immigration policies have become more and more untethered in recent decades in a lust to grow the new industrial for-profit private prison complex. Meanwhile, the American economy still depends on immigrant labor, now more than ever - to feed us, and do the jobs Americans never have, and never will do.

I continue to find ways where I can honor all those who gave up everything for a better life. It is my intent to show here that we can only hope they are being received into a better place than those they knew in their home countries or in our deserts.

Ca nel nehuatl in namoicnohuacanantzin in tehuatl ihuan in ixquichtin in ic nican tlalpan ancepantlaca, ihuan in occequin nepapantlaca notetlazotlacahuan, in notech motzatzilia, in nechtemoa, in notech motechilia …

For I really am your compassionate mother, yours and of all the people who live together in this land, and of all the other people of different ancestries, those who love me, those who cry to me, those who seek me, those who trust in me …

Nican Mopohua, 29-31

Nahuatl version of the apparition of Nuestra Señora to San Juan Diego.

True indeed.

Everything I am and do is rooted in love of our land and its people, and our Mother. Her mantle has room for everyone. And 'She Comes for Them'...

Everything I am and do is rooted in love of our land and its people, and our Mother. Her mantle has room for everyone. And 'She Comes for Them'...

Over the past ten years, more than 4,000 people have died while crossing the Arizona desert to find jobs, join families, or start new lives. Other migrants tell of the corpses they pass—bodies that are never recovered or counted.

Crossing With the Virgin collects stories heard from migrants about these treacherous treks—firsthand accounts told to volunteers for the Samaritans, a humanitarian group that seeks to prevent such unnecessary deaths by providing these travelers with medical aid, water, and food.

Crossing With the Virgin collects stories heard from migrants about these treacherous treks—firsthand accounts told to volunteers for the Samaritans, a humanitarian group that seeks to prevent such unnecessary deaths by providing these travelers with medical aid, water, and food.